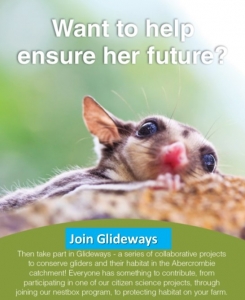

Volplane, steer, brake and anchor. Intriguing words assigned to the habits of one of Australia’s smallest arboreal mammals, the Feathertail Glider.

From Queensland to South Australia, the tiny animal makes its home in the understory of sclerophyll forest where bark and leaves are plentiful for its communal nest building habits.

By day, the Feathertail Glider shelters in tiny tree hollows. By night, it feeds on nectar, pollen and sap with its brush-tipped tongue, opportunistically peppering its diet with invertebrates.

The mouse-sized marsupial has an important ecosystem role: a pollinator, a pest controller and a source of protein for a range of night-dwelling winged and four-footed carnivores.

Adept ly equipped, Feathertails survive often unnoticed in the bush. With its prehensile tail fringed with stiff feather-like hairs providing an extra aerodynamic dimension to its arboreal movements, the glider moves briskly along branches in a series of grips and twists as it catapults through the vegetation, gliding distances of up to 20m. Not bad for an animal measuring 9cm at most.

ly equipped, Feathertails survive often unnoticed in the bush. With its prehensile tail fringed with stiff feather-like hairs providing an extra aerodynamic dimension to its arboreal movements, the glider moves briskly along branches in a series of grips and twists as it catapults through the vegetation, gliding distances of up to 20m. Not bad for an animal measuring 9cm at most.

Impressively, Feathertail Gliders are able to steer and brake their fall, fluttering gently downwards in a leaf-like spiral. Its suction-cupped feet ensuring a gentle and safe landing. It’s those feet that have recently put the glider in the spotlight, revealing not one but two species differentiated largely by the size of their toes.

“Although not yet published, it’s generally accepted that there are now two species of Feathertail Glider,” says Anne Kerle, Ecologist. “Such is the difference, however, that it requires close examination in the hand to tell the two species apart.”

Easier said than done. Feathertails are rarely seen in the wild given their nocturnal habits and swift and often cryptic movements.

“When they are seen, they’re often mistaken for a falling leaf or fluttering moth in the night sky,” Anne says.

“I had opportunity to witness the full range of this animals’ amazing movements at an interstate zoo recently.

“The gliders flung themselves around the nocturnal enclosure, leaping and bouncing from surface to surface, sticking like geckos even to glass,” she says.

The distinction between the two species (frontalis and pygmaeus) has been made primarily on examination of museum specimens, so knowledge of their specific locations and habitat preferences is somewhat lacking.

“This is particularly true in crossover zones such as the Kanangra-Boyd to Wyangala (K2W) Link where habitat extends inland to drier parts and more stunted-forms of sclerophyll forest, but where both species are expected to occur,” Anne says.

“Having a clearer idea of where each species can be found will help plan future Gilder habitat conservation and recovery projects like the K2W Glideways program funded through the NSW Environmental Trust” says Anne.

It’s rare to see a Feathertail in the wild, however, people do come across them. Cats particularly like them, so it’s not unheard of for injured or deceased animals to turn up on peoples’ front lawns.

“While unfortunate for the Glider,” says Anne, “It provides opportunity to collect new Museum specimens to help better-determine the distribution of the two species.”

If you find a Feathertail Glider or have one that comes into care and doesn’t make it, save the carcass by freezing and contact either the Australian Museum or your nearest NPWS office to arrange deposit of the specimen into the Australian Museum collection.

Ensure you record the date and the location the animal came from.

“Providing these details is just as important as the specimen itself,” says Anne.

And for those, like me, who still don’t know what volplane means: It’s a controlled dive or downward flight at a steep angle, especially by an aeroplane with the engine shut off… or Feathertail Glider enjoying a night out in the bush.